What in case you may take an image of each gene inside a dwelling organism—not with mild, however with DNA itself?

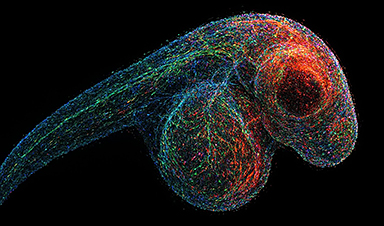

Scientists at the University of Chicago have pioneered a revolutionary imaging technique called volumetric DNA microscopy. It builds intricate 3D maps of genetic material by tagging and tracking molecular interactions, creating never-before-seen views inside organisms like zebrafish embryos.

New Window into Genetics

Traditional genetic sequencing can reveal a lot about the genetic material in a sample, such as a piece of tissue or a drop of blood, but it doesn’t show where specific genetic sequences are located within that sample, or how they relate to nearby genes and molecules.

To address this, researchers at the University of Chicago are developing a new technology that captures both the identity and location of genetic material. The method works by tagging individual DNA or RNA molecules and tracking how neighboring tags interact. These interactions are used to build a molecular network that reflects the spatial arrangement of genes, effectively creating a three-dimensional map of genetic activity. Known as volumetric DNA microscopy, the technique generates detailed 3D images of entire organisms from the inside out – down to the level of individual cells.

Imaging an Entire Organism

Joshua Weinstein, PhD, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Molecular Engineering at UChicago, has spent over a decade developing DNA microscopy, with support from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. In a recent study published today (March 27) in Nature Biotechnology, Weinstein and postdoctoral researcher Nianchao Qian used the technique to produce a complete 3D DNA map of a zebrafish embryo—a widely used model for studying development and the nervous system.

“It’s a level of biology that no one has ever seen before,” Weinstein said. “To be able to see that kind of a view of nature from within a specimen is exhilarating.”

Rethinking Microscopy

Unlike traditional microscopes that use light or lenses, DNA microscopy creates images by calculating interactions among molecules, providing a new way to visualize genetic material in 3D. First, short DNA sequence tags called unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) are added to cells. They attach to DNA and RNA molecules and begin making copies of themselves. This starts a chemical reaction that creates new sequences, called unique event identifiers (UEIs), that are unique to each pairing.

It’s these pairings that help create the spatial map of where each genetic molecule is located. UMI pairs that are close together interact more frequently and generate more UEIs than those that are farther apart. Once the DNA and RNA are sequenced, a computational model reconstructs their original locations by analyzing the physical links between UMI-tags, creating a spatial map of gene expression.

Cell Phones and Cells: A Clever Analogy

Weinstein compares the technique to using data from cell phones pinging each other to determine people’s location in a city. Knowing the cell phone number or IP address of each person is like knowing the genetic sequence of one molecule, but if you can layer on their interactions with other phones nearby, you can work out their locations too.

“We can do this with cell phones and people, so why not do that with molecules and cells,” he said. “This turns the idea of imaging on its head. Rather than relying on an optical apparatus to shine light in, we can use biochemistry and DNA to form a massive network between molecules and encode their proximities to each other.”

Future Applications in Cancer and Immunotherapy

DNA microscopy doesn’t rely on prior knowledge of the genome or shape of a specimen, so it could be useful for understanding genetic expression in unique, unknown contexts. Tumors generate countless new genetic mutations, for example, so the tool would be able to map out the tumor microenvironment and where it interacts with the immune system. Immune cells interact with each other and respond to pathogens in context-specific ways, so DNA microscopy could help unravel those genetic mechanisms. Such applications could in turn guide more precise immunotherapy for cancer or tailor personalized vaccines.

“This is the critical foundation for being able to have truly comprehensive information about the ensemble of unique cells within the lymphatic system or tumor tissue,” Weinstein said. “There has still been this major gap in technology for allowing us to understand idiosyncratic tissue, and that’s what we’re trying to fill in here.”

DOI: 27 March 2025, Nature Biotechnology.

10.1038/s41587-025-02613-z

Additional funding for the study, “Spatial-transcriptomic imaging of an intact organism using volumetric DNA microscopy,” was provided by the Damon Runyon Foundation and the Moore Foundation.